Luca Myers (2021, History) explains his role and routine as a Sidney Organ Scholar.

It is often thought that organ scholars have a strange existence. No one knows the whereabouts of their ‘comfortable’ rooms, nor the hours they keep. Every now and then the haunting sound of the organ can be heard, but whoever plays it remains unseen. They can sometimes be glimpsed scurrying across the court and into the Chapel and it is rumoured that, many years ago, they were even spotted by candlelight at formal hall. No one knows why they do what they do (or how they do it, for that matter). It seems niche, anachronistic and quite odd.

Yet nothing could be further from the truth. Sidney, like most of the older colleges, retains two organ scholars from their undergraduate cohort at any given time. Our duties are to accompany the College Choir or to lead it in the absence of the Director of Music. The choir sings thrice weekly in Chapel and meets for one additional rehearsal to complete the cycle.

The organ scholars are at the heart of the Choir, which itself is at the heart of the College. As term presses on, noisy and unrelenting, Chapel services punctuate each week with an admixture of virtuosity and calm. This particular feather in the College cap, however, requires practice. Organ scholars must find the time to disentangle themselves from the tribulations of academia, in order to isolate their focus on the organ. There is no typical day at Cambridge, not least for its small band of organ scholars. I will always remember the advice I received from an alumnus of Sidney, who served as one of the first organ scholars under current Director of Music, Dr Skinner, who said thus: ‘Rise at seven, and play for two hours. Then, you have the day ahead of you to do as you wish.’ I was stunned, and in any case stopped listening after the preposterous remark ‘Rise at seven’. I thought to protest the point with a verse of Psalm 127 – ‘God grants sleep to those he loves’– but thought better of it.

But we do (try to) play daily. Most organ scholars study music or a humanity of some description (I study History), and it is not difficult to find the time to practise. Lectures are early, and contact hours relatively few, often permitting free hours during the day and certainly in the evening. I practise little and often, in Michaelmas Term more often than little, but in Easter Term more little than often. Practice, and the choir’s weekly cycle, gives, believe it or not, rhythm to the rather fluid existence of a humanities student.

Practice is rarely a chore but rather a welcome change of pace from my books. The rewards and fulfilment come every Wednesday, Friday and Sunday, when the choral and organ scholars meet to perform a cherished musical tradition to a famously high standard. But even choral purists like me need more incentive than the cultural and spiritual profit of music-making. For this, twice-weekly dining rights go a long way, and further still the preferential accommodation reserved for organ scholars. No amount of glorious English ‘Victoriana’ can do quite what a free dinner on a Friday can.

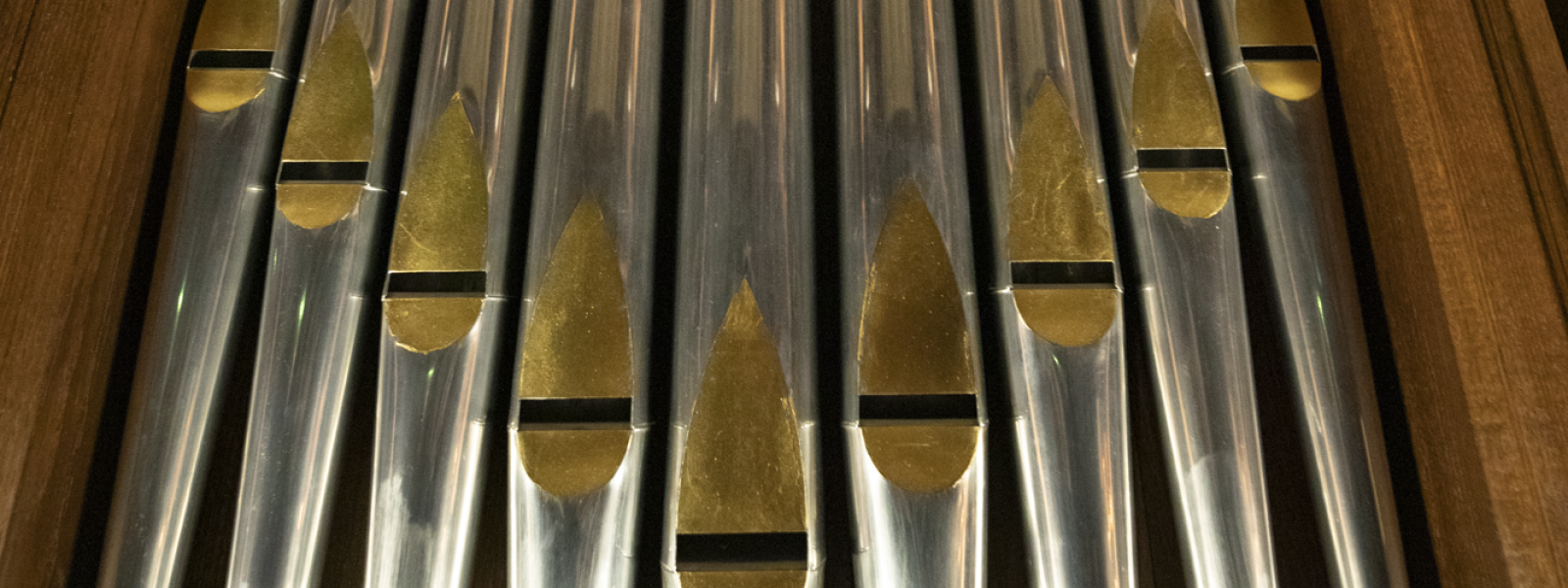

That, then, is the life of an organ scholar. We exist and we toil, even if it is unseen. Within the memory of each Sidney member are some favourite moments. Among these are no doubt the service of matriculation, the carol concerts at ‘Bridgemas’, and the ceremony of graduation. At every one there will be, lofty and out of sight, an organ scholar tinkling away. Sidney’s choral tradition is as old as the College itself. Under Dr Skinner the Choir is not only the best it has ever been but also casts even its most illustrious competitors in the shade. Behind a substantial part of this success lies the dedication of its organists. I am proud to hold the organ scholarship, and to take a leading role in the Choir that does so much to spread the College’s historic reputation for excellence.