To mark World AIDS Day 2023, we spoke to Sidney alumnus and HIV and AIDS expert Dr Tristan Barber (1996) about his more-than-two-decades of work in this field, the progress made in terms of treatment, and the evolving challenges facing people living with HIV.

Background: the HIV epidemic

In June 1981, the US Center for Disease Control reported that hospitals in Los Angeles had dealt with five recent cases of Pneumocystis Pneumonia, a medical condition ‘almost exclusively limited to severely immunosuppressed patients’. Two of the five people affected, all of whom were gay men, had died.

By the following May, the CDC had received reports of 355 cases of opportunistic infections ‘occurring in previously healthy persons between 15 and 60 years of age.’ A significant number of those affected were suffering from Kaposi's sarcoma, a rare skin cancer producing purple tumors.

Just two years after that first CDC report, the new disease was being described as ‘the No. 1 priority’ of the US Public Health Service. However, many in positions of power would fail, for many years, to fully engage with a disease they felt would primarily affect already-marginalised groups (the LGBTQI+ community, intravenous drug users and Haitians living in the US).

Many media outlets also failed to report on the new disease, despite its growing toll. When they did, the coverage of many served to undermine public understanding and reinforce existing prejudices: false claims that the new disease was highly contagious created a climate of fear (a problem many felt was compounded, years later, by ‘doom-laden’ public health campaigns); homophobic attitudes underpinned a ‘blame game’ - the New York Times Magazine referred to the heterosexual victims of AIDS as ‘innocent bystanders’; in the UK, papers including the Mail on Sunday and The Sun referred to a ‘Gay Plague’ and Sir James Anderton, the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester, was allowed to remain in post despite describing victims as living in a ‘human cesspool of their own making’.

Actions have consequences – the false claims made about the new disease, and responsibility for it, fueled attacks on the queer community, led to people being sacked from their jobs and evicted from their homes, and directly affected the care provided to the dying. At the same time, in the US, Virginia Apuzzo, Executive Director of the National Gay Task Force, complained that the queer community had been ‘systematically… eliminated from any discussion of public policy’ in relation to the virus, ‘especially as it relates to our lives.’

Today, 40 years later, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) remains, according to the World Health Organisation, ‘a major global public health issue’. AIDS - the illness that results from untreated HIV – has killed an estimated 40 million people worldwide.

While the WHO continues to note ‘ongoing transmission in all countries globally… with some countries reporting increasing trends in new infections when previously on the decline,’ the past four decades have brought real progress in the treatment of people living with an HIV diagnosis.

In 1996, research established the effectiveness of triple combination therapies in suppressing the virus, a discovery that would transform the life chances of those affected.

Our expert: Dr Tristan Barber

Consultant Physician Dr Tristan Barber, an international expert on HIV and AIDS, recalls the temporary job in the summer of 1996 that, in part, sparked his interest in this area: ‘I was actually working at the Royal Free as a medical secretary in my summer holidays, and writing letters about people who were living with HIV and on the older two-drug therapy’.

‘The doctors had just come back from the World AIDS Conference in Vancouver, and I remember their excitement about viral suppression and the new cocktail of drugs that were going to turn people's lives around. That was the first time I thought I might have found a medical specialty I could work in.’

Moving to Sidney for his clinical training, Tristan pursued his elective on an HIV ward at San Francisco General Hospital where, in 1983, doctors had established the first outpatient clinic for people with AIDS, and then developed the influential San Francisco Model of Care. He then gained experience in the treatment of paediatric HIV at Great Ormond Street, London.

Having enjoyed stints working in A&E, and in obstetrics and gynaecology, he says, ‘I then got a sexual health and HIV job and absolutely loved it. The sexual health work was fantastic, and all the people with HIV on the ward, which was at Barts, were late diagnosed - very complex, very acute, and medically interesting. I realised that although I'd been trying out different things, sexual health and HIV was calling me back.’

By 2016, three large-scale research studies, focusing on couples living with HIV, had established that, in the words of UNAIDS, ‘A person with an undetectable viral load has no chance of passing on HIV.’ This confirmation of the effectiveness of triple combination therapies in limiting transmission promoted the ‘undetectable = untransmissible’ or ‘U=U’ campaign. By 2019, the National AIDS Trust noted,‘97% of those engaged and on treatment (in the UK were) virally suppressed which means they can’t pass the virus on.’

Since 2018, Tristan has been based at the Ian Charleson Day Care Centre at the Royal Free Hospital, London. The clinic, named after the Chariots of Fire star who famously requested that his cause of death – AIDS - be publicly confirmed to raise awareness, provides holistic care to those living with HIV.

If we include that summer job, your own involvement with people living with HIV runs from those first real signs of hope, fifteen years in, to a very different situation now, where an early diagnosis and treatment should lead to normal life expectancy. In the early days of the epidemic, the psychological impact of an HIV diagnosis was profound – is that still the case?

‘So, in my head, I split people with HIV into four groups. There are the people who were diagnosed before 1996 - these are the people who may have an element of post-traumatic stress disorder, who have lost friends and partners, and were told to stop working. They were told to sell their house, cash in their pension, and do the bucket list, perhaps told their life expectancy was five to ten years. Many have had a long period of being immunocompromised and have also had distressing AIDS-related diagnoses, or cancer, in addition to HIV.

‘From 1996 to 2005 things got a bit better. They would have been put on triple therapy, but the drugs were still pretty toxic.

‘I would say that the people in those first and second groups are the ones that we need to still have a very heightened lens on, in terms of looking out for complications physically, psychologically, and socially.

‘From 2005 to 2015, the drugs were a lot better, and we started treatment at a much earlier stage, if we picked up that they had HIV. So, people generally did much better - they started to live with HIV, rather than HIV being a dominant presence in their lives.

‘And then from 2015 onwards, we've had the results of a study called the START Study, which means that we put everyone with HIV on to treatment regardless of where their immune system is at. And those people are progressing with their lives in a much more normal way, generally. They still suffer, of course, with stigma and some of the psychological burdens of having an HIV diagnosis.

‘So, that’s a very crude way of dividing people up, but people in those four groups have often had a very different life experience and journey with HIV. A lot of the press has been around the successes and the falling numbers, the fact we now have pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and the fact that people with an HIV diagnosis have a normal life expectancy. But I think we mustn't forget the stories of those people who are still here, who were diagnosed or who acquired HIV before there was any successful treatment.’

And it’s clear that the ignorance and stigma remains.

‘Yes, it really does.

‘There's still an assumption, if you look at the surveys, that people affected by HIV are either from certain ethnic groups, or they inject drugs, or they are gay and bisexual men.

‘Men who have sex with men, in particular, they're very HIV literate, they understand the fact that being undetectable on treatment means you can't transmit your virus sexually. They understand how to protect themselves with pre-exposure prophylaxis. They really know where we're at with the modern science of HIV.

‘But what we're seeing now, in terms of new diagnoses, are middle-aged heterosexuals who've never thought about HIV, never thought about testing, whose ideas about HIV are at least 20 years old.

‘And so we're seeing a whole different type of stigma actually, because these are people whose friends don’t talk about HIV, they don’t know about the successes of HIV treatment. And so the need for education is like a step back in many ways, to where we were a decade or two ago.

‘So, those assumptions still need challenging. It's very clear that HIV can affect anyone - it's an infection, not a judgement.’

In addition to the stigma, there is discrimination, and it’s important to note that many of those at greatest risk of HIV infection are also subject to other forms of discrimination.

‘Yes, intersectionality is really important. People who are at risk of HIV often face a lot of issues around intersectional discrimination and stigma, and those issues can, of course, become worse when they have a new HIV diagnosis.

‘I have to say, we're very lucky in the UK, in that HIV care is free for everyone. So, even if you're an undocumented migrant, you can present to an HIV service and receive free treatment. However, what's clear is that not everyone is aware of that, and some people - because of stigma, because of fear - may not come forward for treatment.

‘It’s estimated that there are about 5,000 people in the UK who are not aware they are living with HIV.

‘For that reason, I think it's very important that we normalise testing, in a variety of settings, because we know that if we wait for people to come to us to test, we won't find all the people who are living with HIV.’

In addition to your clinical work, you Chair the Board of Trustees for the peer support charity Positively UK. Why is it important to hear that patient voice?

‘So, through my work with Positively UK, but also through my involvement with something called the People's First Charter, established by my friend and colleague Dr Laura Waters, we've really started to think about individuals and their lived experience with HIV.

‘With Positively UK, the peer support is provided by people with lived experience of HIV, and this can be tremendously important to people at the time of a new diagnosis, but also to those who've been living with HIV for many years.

‘If someone has had a fairly recent diagnosis, they may not understand all the language; they may feel intimidated in terms of asking the difficult questions.

‘When they sit with someone who looks like them, who sounds like them and who has real lived experience, they often open up in a way they can't do in a more medicalised setting. We know from the feedback we’ve received that for many people having that peer support is incredibly important.’

People living with HIV now have a normal life expectancy. Has it been necessary to adapt your services to deal with that ‘ageing population’?

‘Yes, so, in the UK, more than 50% of people living with HIV are now over 50. So, we have to adapt our services to meet their needs.

‘Some cancers occur more frequently or more severely in people who are HIV positive; some types of dementia or cognitive impairment might appear a little bit earlier; people living with HIV are definitely at a higher risk of cardiovascular disease; and HIV can also affect other organ systems.

‘A few years ago, we established a dedicated ageing and frailty service here at the Royal Free, called the Sage Clinic, with HIV input from me, alongside our fantastic geriatrician lead, Dr Howell Jones.

‘In addition to the frailty service, we also have an integrated cardiology and renal service; we have a surgeon who does a clinic for people with HIV; we have a liaison psychiatrist and a great psychology team; we also have an endocrinologist and a rheumatologist who do clinics within the HIV service, and other specialists also.

‘We have joint clinics to try and anticipate some of those problems early, particularly in our older cohort of people living with HIV.

‘And it's not just about people that are chronologically old, it's about people that are “HIV old” as well. You might be a 70-year-old who was diagnosed in 2017 and acquired HIV recently. Your journey will be very different to someone else who's 70, but who was diagnosed in 1987 or 1992. So, we have to think about the individual’s “HIV age” as well as their actual age.’

AIDS remains a global epidemic; we are emerging from the COVID pandemic: attempting to treat one virus, in the context of another, must have required a lot of thought.

‘Yes, well, for the people we see that have been living with HIV for longer, COVID triggered some really awful memories of the early days of the HIV epidemic.

‘The worst thing was that we were slowly getting back to normal, and then suddenly there were the first Mpox cases, and we went back to having to put people into quarantine and to wearing lots of PPE to take samples and to see them.

‘That was awful - suddenly they were being isolated again. So, yes, it was a very difficult time.

‘However, one positive is that some of the mRNA vaccines that were developed for COVID, the same technology is being used to look at an experimental HIV vaccine, and the hope is that that might have greater success with that vaccine than with some of the attempts to date.’

So, looking ahead – what’s next?

‘We continue to expand our research projects. One I am involved with is a pan-European project looking at ways to improve HIV testing, which will build on our successes in the last 18 months of offering opt-out screening for blood-borne viruses in our Emergency Department.

‘I’m very excited to be involved in finding better ways to identify those living with HIV, so they can benefit from treatment, and to help us meet the UNAIDS target of no new HIV transmissions by 2030.

‘Not only is having an undetectable amount of HIV in their blood (an “undetectable viral load’’) good for an individual living with HIV, it also means they cannot transmit their virus sexually. This has led to the U=U or 'undetectable equals untransmissible’ statement, which has been life changing for people living with HIV.’

Dr Tristan Barber MA MD (Cantab.) is a Consultant in HIV Medicine, Honorary Associate Professor at UCL Global Health, Honorary Secretary of the British HIV Association, Chair of the Board of Trustees of Positively UK, and Chair of the EACS Young Investigator Network at the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS).

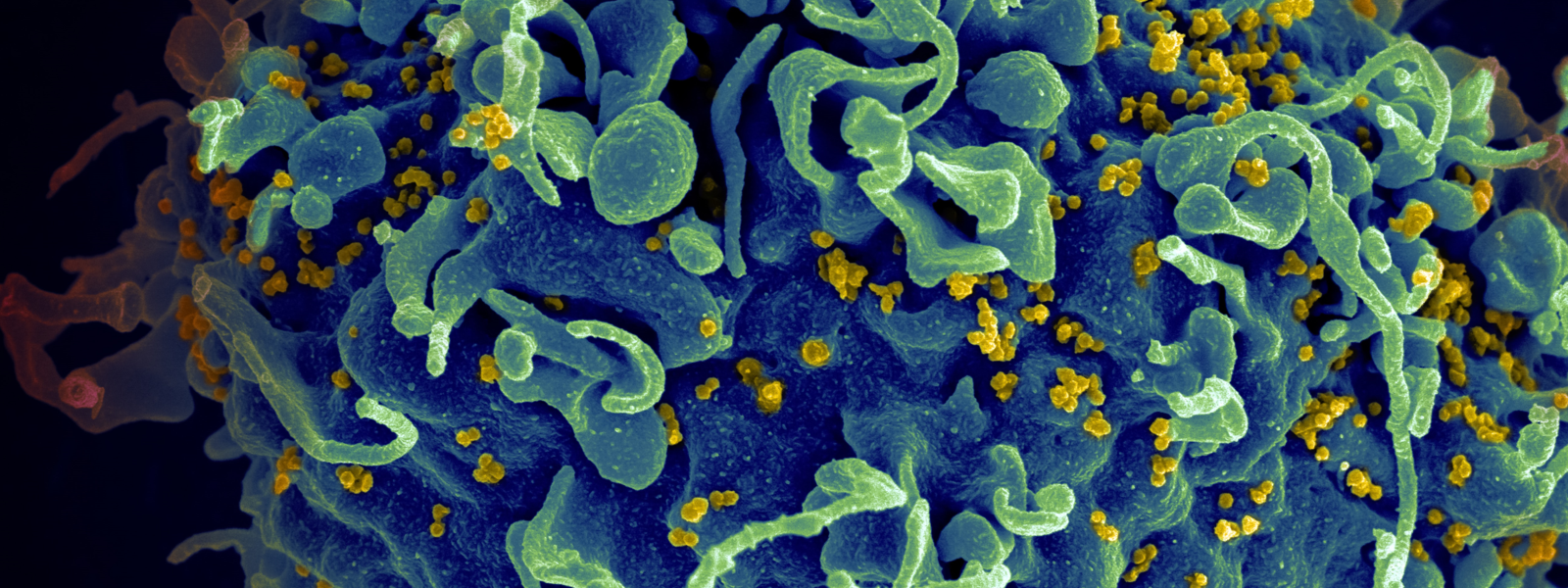

Banner image: National Cancer Institute

If you have something that would make a good news or feature item, please email news@sid.cam.ac.uk